After nine and a half hours of driving, the last hour on well-maintained gravel roads in the middle of nowhere, Wyoming, I finally reach the trailhead. I see a dusty HistoriCorps sign and follow it around to a corral with a Forest Service truck and livestock trailer and a HistoriCorps truck and cargo trailer parked out front. Whew, I really did make all the right turns. The road to Jack Creek Campground is not well marked.

Walking over to the corral, I’m met by a young woman with a friendly smile and exuberant brown hair, and a young man with an equally friendly, but more intense smile and even more exuberant curly red hair and beard. We exchange names, theirs are Charlotte and John, and confirm I’m 1) the first to arrive, and 2) the only Team Rubicon member coming, except possibly a man named Corey. I’m skeptical because I know my teammate, a female Korey, can’t come because of work requirements. I’m disappointed to find out all the other TR people have backed out as well, but with so many being wildland firefighters, it’s not surprising.

Before too long, the other two volunteers arrive. Marty and Dave are retired engineers, civil and structural respectively, from Colorado. We all kick back in the corral’s bunkhouse with a semi-frosty beverage and discuss the hitch with Forest Service mule packer Harley—and his dog, a blue heeler mix named Granite. We’ll be camping at the trailhead tonight; the trip leaders recommend sleeping in our cars. Which works for me—my Subaru is pretty comfy for a single person. I’m not sure Marty and Dave will be as comfy with two of them in their Outback—theirs is blue versus my green—but that’s their decision.

After a fairly comfortable night, we have a quick breakfast and I eagerly pull my personal gear out of my backpack. The packers have room to bring most of our stuff up; I’m thrilled to have a mule pack my work clothes and camping gear. We spend the next hour mostly watching the packers—there’s now four of them and a lot more mules and horses—divide the gear into equally weighted panniers and piles. If you’ve never seen the process before, it’s interesting; the weights on either side of a mule must be balanced within a pound, or the mule will be too unstable on the trail. There’s a lot of shuffling and repacking before the train is loaded and on their way. Horses move at about three miles per hour, so they’ll arrive well before us, dump our gear and most likely run into us on their way back.

I’m happy my backpack is light because one of the first things we do is ford the Greybull River on our way into the Washakie Wilderness in the Shoshone National Forest. The river isn’t raging, but it’s still fast, wide and cold. But the day is blistering hot, so starting out with cold feet is not a bad thing. The first half of the hike is fast, with gently rolling trail, trending up, in a really interesting landscape. There are towering, desert-dry cliffs around us, but the riverbed is lush and green enough to support moose. John spots a mama and baby moose—fortunately on the far side of the river since there are few animals as dangerous as moose. I’d rather confront a grizzly bear than a mama moose.

The first four miles pass quickly. Then we turn into an unmarked side canyon trail and head up—way up. The last two and a half miles are much steeper and slower, and I’m not the slowest one for once! But I’m happy to hang back because the canyon is beautiful, there are wild raspberries growing here and there, and I know exactly how it feels to be the slow person in a group. We do indeed meet the mule string on their way down—unfortunately, at the very steepest part of the trail.

We finally reach the Anderson Hired Hands Cabin, our main project. It’s a small, single story cabin, with a brand-new porch built by the last group and a whole lot of stuff inside. We continue to a plateau beyond the cabin where we’ll set up our tents, and on to the Anderson Cabin itself, which is about a quarter of a mile from the Hired Hands Cabin. There we meet another group—this one archeologists exploring the early native American artifacts in the area. Greybull River Sustainable Landscape Ecology (GRSLE) project seeks a deeper understanding of the prehistoric, the historic/contemporary, and the series of possible futures in this landscape. They’re led by Larry Todd, Colorado State University professor emeritus of anthropology, who feeds his band of retirees and students on a carefully planned calorie load of commercial freeze-dried meals and single-slice packages of Spam.

After hearing this, I’m thrilled to find out Charlotte, our camp cook and co-leader, has no intention of following Larry’s lead. No, our meals throughout this eight-day hitch are fabulous, with fresh vegetables and inventive, delicious combinations. I’m happy to play sous chef for dinner and even happier to eat. Working with hand tools at 7,500 feet gives you a big appetite.

We set up our gear and organize the cook tent and group area. By the end of the day, I’m exhausted, and I’m asleep by 9:00 p.m. The next day we organize and clean the Hired Hands Cabin (HHC). Cleaning takes longer than expected because there are a lot of mouse droppings, so we wear masks and wet the area down with a bleach solution before sweeping. We also do some daubing, which is filling the cracks between the logs with a mixture of sand, lime and Portland cement, to make the cabin a little more weather-proof. The Forest Service intends to use the HHC as an emergency shelter, so anything we can do to tighten the structure is good.

That afternoon, we investigate the stability of the Anderson Cabin. Anderson was the first Superintendent of the Forest Service and his cabin is large and very well appointed for a log structure. The native stone fireplace is a thing of beauty. Unfortunately, the rest of the cabin hasn’t fared as well. The entire structure is very oddly constructed and extremely unstable. Dave, who spent most his career in mining and investigating mining accidents, is extremely concerned about safety of the tentative HistoriCorps plan. Jacking and shoring this cabin will not be easy or quick and may not be possible at all, especially with volunteers and hand tools. Marty and I agree wholeheartedly with Dave. It’s not the answer anyone wants to hear, but it’s the right answer. The safe answer.

The next day, we re-hang the very heavy two-piece HHC door and plan out the design of the new threshold. Because of the cabin floor and door, it’s going to be a very high threshold, a potential tripping hazard, but leaving a huge gap isn’t a good solution either. John and I cut a log—okay, John does most of the cutting—and make the initial splits with a huge chisel and felling wedges. We also start taking apart a corner cabinet that’s become a giant mouse house. It’s built out of tongue and groove beadboard and lined with metal mesh to keep mice out, but unfortunately, the mesh became a perfect place for mice to nest between the mesh and logs. It’s a long laborious process because it has to be sprayed with bleach water to prevent any of us contracting hantavirus.

After lunch, I start fitting the two window frames. The packers carefully brought in the glass, which will be installed after the frames can be secured. It takes me most of a day to fit the west window, because one corner needs to be carved off, and the others need shims. It takes another full day to fit the south window, which needs a lot of big shims. These tasks would be relatively simple with power tools but doing it by hand with chisels and hand saws is a much more involved process. It’s also extremely satisfying.

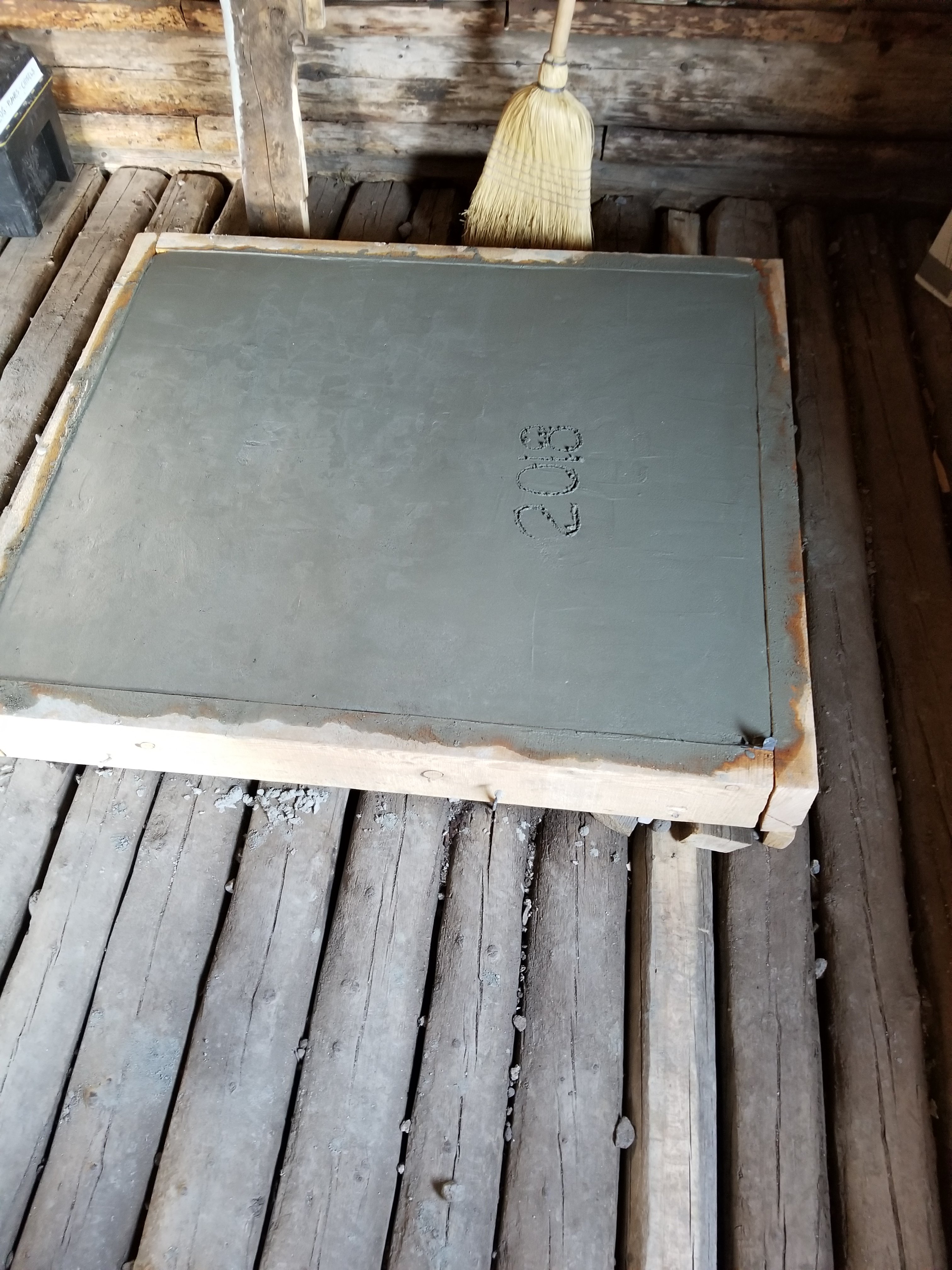

While I’m working on the windows, and Char on the door latch, the guys start discussing how to rework the wood stove pad. The existing concrete is crumbling and too small. After pulling the old boards off the pad, the guys discover the original pad was reinforced with horse shoes and barbed wire. Which is really cool. But it sparks a very long, involved discussion about the relative merits of various concrete mixtures, whether they have enough cement, using more barbed wire as reinforcement and how big and thick the renovated pad should be. Char and I smirk as the discussion winds on and on—a typical engineer debate. Come on guys, it’s a stove pad, not a bridge. They finally decide on size, materials, and design, but it’s too late to start now.

The next days passed in a similar fashion. John installs the stove pipe on the roof, the concrete gets poured, with fabulous barbed wire reinforcement by Marty, the interior daubing gets done by the guys, the stove gets installed despite bad instructions, and the corner cabinet gets reconstructed as an open cabinet. I get the windows fitted, so Char installs the glass. I try to finish the threshold, but in the end, my poor right wrist can’t take any more pounding of mallet on a chisel, so Char finishes it off too. John and Dave fire up the stove and it draws perfectly, warming the small cabin immediately. Unfortunately, they also discover the stove bottom is cracked! It should be fine for small fires, but the Forest Service will have to replace it sooner rather than later. Hopefully with a slightly smaller model—this one is way too big for the cabin.

On our fifth day in the wilderness, we have an early dinner and take off on solo hikes. I hike to the rocks above our tents, then over to the next ridgeline. Between my destinations, I get buzzed by a red-shouldered hawk, swooping lower every pass, to about 15 feet from my head. It veers off when I announce my hat isn’t a good snack. Dave, who goes hiking by himself every morning before we work, has seen lots of elk and an antelope. Upstream from us, Larry tells us his chocolate lab Tao warns him of a grizzly sow with two cubs, but the rest of us don’t see any bears, which is just as well.

On our last full day, we finish all the projects while Dave and Marty install the shutters. John and I clean up around the HHC while Char cleans up the storage in the Anderson cabin, secures everything for the next season’s work and prepares an early dinner, including a side dish of archeologist. They’re happy to have a real meal. We all work together to take down the cook tent and pack everything into bear-proof panniers for transport back out of the wilderness. John and Char seem happy with our progress, since they’ve completed all their contracted work plus some extras, so our final night is lighthearted and fun.

On our last night, we get our first bad weather, a rainstorm. Fortunately, it’s not too bad, the lightning stays out of our valley, and it quits before morning. We’re up extra early the next morning for a fast breakfast of coffee and bagels. We pack up our gear, our wet tents and start down the trail. We have to carry all our gear down, but still, it’s a pretty easy hike since it’s mostly downhill and we’re not carrying food. We’re within a mile of the trailhead when the pack string meets us—they’ve brought four packers and fifteen mules to get the HistoriCorps and archeologist gear out in a single trip.

At the trailhead, we exchange swag—HistoriCorps mugs and Team Rubicon patches and stickers. We all drive into Meeteetse for lunch at a local bar and a trip to the local fine chocolate shop. Yes, there’s a fine chocolate shop in a tiny Wyoming town of fewer than four hundred people. After lunch, we all say our slightly sad goodbyes—I’m headed north, then west. Dave and Marty are headed to Denver but are stopping at the hot springs at Thermopolis on the way, while John and Char head back to the trailhead to get the gear packed up. They’re going to Teton National Park for the next project, one with five sessions extending into October. Maybe I’ll talk the Amazing Sleeping Man into joining me for one of the later sessions—it might be fun, if chilly.

As with most backcountry trips, leaving all my new friends is sad, but I can hardly wait to see my husband, sleep in my own bed, and take a shower! I’m pretty sure I’ll see some of these people again—I had a great time and look forward to another HistoriCorps trip. The trip leaders are professional, knowledgeable and fun and the work is satisfying.

If this trip sounds intriguing, anyone with an interest in restoring old buildings can volunteer for HistoriCorps. There’s a variety of trips and projects; you can find one to suit your interests. Some allow older children to help with their parents. If you’d like to see the Anderson Cabin, make sure you stop and talk to a Shoshone National Forest ranger, because the turnoff up to the cabin isn’t marked; you’ll need a map.

Oh, and a huge trip bonus? I lost those last few Houston pounds!

Copyright (c) August 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED